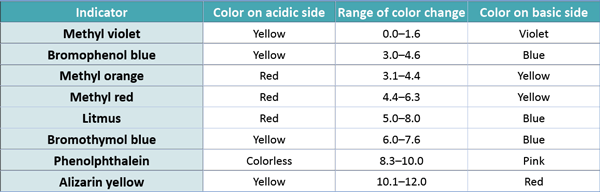

A typical titration begins with a beaker or Erlenmeyer flask containing a very precise volume of the analyte and a small amount of indicator placed underneath a calibrated burette or chemistry pipetting syringe containing the titrant. Small volumes of the titrant are then added to the analyte and indicator until the indicator changes, reflecting arrival at the endpoint of the titration.

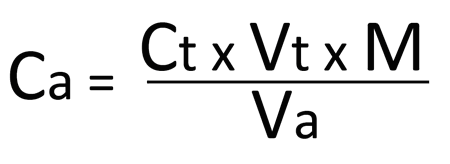

Depending on the endpoint desired, single drops or less than a single drop of the titrant can make the difference between a permanent and temporary change in the indicator. When the endpoint of the reaction is reached, the volume of reactant consumed is measured and used to calculate the concentration of analyte by:

Cais the concentration of the analyte, typically in molarity;

Ct is the concentration of the titrant, typically in molarity;

Vt is the volume of the titrant used, typically in liters;

M is the mole ratio of the analyte and reactant from the balanced chemical equation;

Va is the volume of the analyte used, typically in liters.

There are many types of titrations with different procedures and goals.

The most common types of qualitative titration are acid-base titrations and redox titrations.

Acid-Base Titration:

Karl Fischer titration is a classic titration method in analytical chemistry that uses coulometric or volumetric titration to determine trace amounts of water in a sample.